The strange history behind five everyday Italian words

If you make even a slight effort to speak Italian, chances are you’ll have uttered at least one of these already today.

But you probably weren’t aware of the strange story behind how that word came to be.

Just like every other aspect of its culture, from architecture to food, every word in the Italian language bears traces of the country's long history. Here are the strange stories behind five everyday words.

Ciao - hi/bye

Probably the most famous word in the Italian dictionary, the informal greeting has been exported all over the world. But you may not have realized that it comes from the term 'schiavo' (slave). The Latin greeting 'servus humillimus' ('your obedient servant) was used when speaking with a superior, and in Venetian dialect this became 's-ciao vostro' - literally translating as 'your slave'.

READ ALSO:

However, 'schiavo' doesn't come from 'servus', but from the Latin 'sclavus' ('slave'), which is thought to have its origins in the term 'Slavic', as this was the ethnicity of most slaves at the time. Over the years, the 's' was dropped from 's-ciao', giving us the modern form 'ciao' - which is no longer seen as having any deferential meaning or reference to ethnicity, and is used as an all-purpose informal greeting.

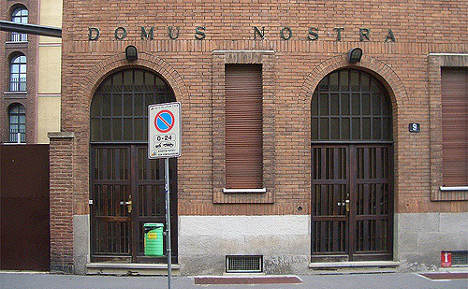

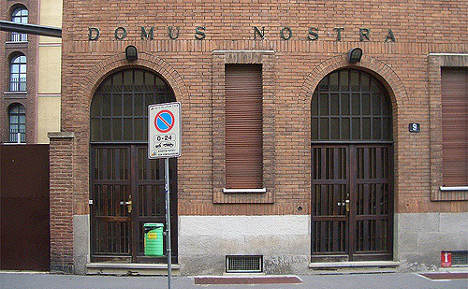

Casa - house

Photo: Katrin Svabo Bech

In Latin, the word for house was 'domus', and this term has left traces in modern Italian in words like 'domestico' ('domestic'), as well as in Sardinia, where 'domo' means 'house' (the Italian dialects are, in fact, not descendants or variants on standard Italian, but languages which evolved independently from Latin). 'Casa' existed in Latin too, but it referred to a cottage, hut or hovel. So how did it come to mean 'house'?

READ ALSO:

The answer for this is that when people began building cathedrals in the Middle Ages, they needed a word to distinguish them from plain old churches. Instead of coming up with a new term, they just borrowed an existing word, calling them 'domus dei' (God's house), which was soon shortened to 'domus'. But this led to a new problem as they were left without a word for ordinary houses. As more people were moving to the growing towns, there was less of a need to talk about huts and hovels, so they started using 'casa' to refer to ordinary houses.

As for how 'domus' became 'duomo', the final 's' was lost over the years like the 's' in 'sclavus'. In Latin, consonants were used to distinguish the case of a word, but Italian lost the case system and used things like prepositions to show a word's role in the sentence. The 's' was no longer necessary and was eventually lost because words, like landscapes, often erode over time.

Donna - woman

Photo: Monica Sportelli

'Domus' has left other traces in the language too; 'donna' comes from Latin's 'domina', meaning 'mistress of the house', which has a clear root in 'domus'. 'Donna' is another eroded form; try saying 'domina' really fast lots of times to see how linguistic erosion turned the middle syllable 'min' into a double 'n'.

In medieval times, 'donna' was a term of respect, equivalent to 'noblewoman', while 'femmina' was the general term used for 'woman', derived from the Latin term for breastfeeding. In Sicilian, 'fimmina' is still used for 'woman', but in standard Italian, 'femmina' is usually only used to mean 'female' in the sense of biological gender, for example to distinguish the sex of animals. 'Donna' is the default word for 'woman'.

READ ALSO:

The reason for this is probably because standard Italian has its roots in the courtly love poetry of the likes of Dante. When scholars were trying to choose one of Italy's many dialects to become its standard language, they were drawn to Florentine because they thought that the many great literary works in Florentine had ennobled this dialect. Dante and co. liked to refer to their muses as 'donne' as a way of praising them. In Dante's Commedia for example, 'femmina' is used far less than 'donna' and only ever in Hell and Purgatory - it is strongly linked to the woman's flesh identity rather than her mind or soul.

In standard Italian, 'femmina' still has a slightly derogatory sense - so for example you might hear an Italian man disgruntled with his romantic life complain that he has met plenty of 'femmine' but few 'donne'.

Testa - head

If you’ve travelled around Italy a lot, you may have noticed that dialects in certain regions use a different word for head - ‘capo’. This comes from Latin ‘caput’, which also meant head, but in standard Italian ‘capo’ is generally used in a non-anatomical sense, for example to refer to a boss or head of department, while 'testa' refers to the body part.

The word ‘testa’ did exist in Latin, but it meant a piece of clay or pottery fragment and derived from 'texō' (to weave, to do woodwork). Over time, its meaning got extended so that it could refer to a whole pot as well as just a fragment. Then one day, someone realized that with its round shape and two side handles jutting out like ears, a Roman pot resembled a human head, so in vulgar (spoken) Latin that's what 'testa' came to mean.

Cattivo - bad

Photo: Nikki McLeod

Anyone who's tried to get to grips with Italian grammar will be well aware that ‘cattivo’ is an irregular adjective, because in adverbial form it becomes ‘male’ rather than adding the suffix ‘mente’, like most adjectives do. The origin of ‘male’ is easy to trace; it comes directly from Latin ‘malus’ (bad), so why do we now say ‘cattivo’?

In Latin, captīvus meant ‘captive’ or ‘prisoner’ (the verb ‘catturare’ (to capture) derives from the same word) but its meaning morphed over the years. ‘Cattivo’ came to mean ‘bad’ not because prisoners themselves were associated with bad behaviour, but because of the expression in Latin Christian texts 'captivus diaboli' (prisoner of the devil), referring to damned souls and sinners. You might have noticed that religion had a huge influence on the development of the Italian language, and it's no surprise since most early texts were religious and most of the earliest writers were monks.

Understanding the etymology of 'cattivo' may be helpful to foreigners trying to get their heads around where to put it in a sentence. When it follows the noun, it retains its original moral meaning ('bad' in the sense of 'evil'), so ‘un attore cattivo’ is a wicked actor, bad to their core. When 'cattivo' precedes the noun, it has a more general sense and refers directly to the noun - so ‘un cattivo attore’ might be a morally good person, but hopeless at learning their lines.

This article was originally published in 2016.

Comments

See Also

But you probably weren’t aware of the strange story behind how that word came to be.

Just like every other aspect of its culture, from architecture to food, every word in the Italian language bears traces of the country's long history. Here are the strange stories behind five everyday words.

Ciao - hi/bye

Probably the most famous word in the Italian dictionary, the informal greeting has been exported all over the world. But you may not have realized that it comes from the term 'schiavo' (slave). The Latin greeting 'servus humillimus' ('your obedient servant) was used when speaking with a superior, and in Venetian dialect this became 's-ciao vostro' - literally translating as 'your slave'.

READ ALSO:

However, 'schiavo' doesn't come from 'servus', but from the Latin 'sclavus' ('slave'), which is thought to have its origins in the term 'Slavic', as this was the ethnicity of most slaves at the time. Over the years, the 's' was dropped from 's-ciao', giving us the modern form 'ciao' - which is no longer seen as having any deferential meaning or reference to ethnicity, and is used as an all-purpose informal greeting.

Casa - house

Photo: Katrin Svabo Bech

In Latin, the word for house was 'domus', and this term has left traces in modern Italian in words like 'domestico' ('domestic'), as well as in Sardinia, where 'domo' means 'house' (the Italian dialects are, in fact, not descendants or variants on standard Italian, but languages which evolved independently from Latin). 'Casa' existed in Latin too, but it referred to a cottage, hut or hovel. So how did it come to mean 'house'?

READ ALSO:

The answer for this is that when people began building cathedrals in the Middle Ages, they needed a word to distinguish them from plain old churches. Instead of coming up with a new term, they just borrowed an existing word, calling them 'domus dei' (God's house), which was soon shortened to 'domus'. But this led to a new problem as they were left without a word for ordinary houses. As more people were moving to the growing towns, there was less of a need to talk about huts and hovels, so they started using 'casa' to refer to ordinary houses.

As for how 'domus' became 'duomo', the final 's' was lost over the years like the 's' in 'sclavus'. In Latin, consonants were used to distinguish the case of a word, but Italian lost the case system and used things like prepositions to show a word's role in the sentence. The 's' was no longer necessary and was eventually lost because words, like landscapes, often erode over time.

Donna - woman

Photo: Monica Sportelli

'Domus' has left other traces in the language too; 'donna' comes from Latin's 'domina', meaning 'mistress of the house', which has a clear root in 'domus'. 'Donna' is another eroded form; try saying 'domina' really fast lots of times to see how linguistic erosion turned the middle syllable 'min' into a double 'n'.

In medieval times, 'donna' was a term of respect, equivalent to 'noblewoman', while 'femmina' was the general term used for 'woman', derived from the Latin term for breastfeeding. In Sicilian, 'fimmina' is still used for 'woman', but in standard Italian, 'femmina' is usually only used to mean 'female' in the sense of biological gender, for example to distinguish the sex of animals. 'Donna' is the default word for 'woman'.

READ ALSO:

The reason for this is probably because standard Italian has its roots in the courtly love poetry of the likes of Dante. When scholars were trying to choose one of Italy's many dialects to become its standard language, they were drawn to Florentine because they thought that the many great literary works in Florentine had ennobled this dialect. Dante and co. liked to refer to their muses as 'donne' as a way of praising them. In Dante's Commedia for example, 'femmina' is used far less than 'donna' and only ever in Hell and Purgatory - it is strongly linked to the woman's flesh identity rather than her mind or soul.

In standard Italian, 'femmina' still has a slightly derogatory sense - so for example you might hear an Italian man disgruntled with his romantic life complain that he has met plenty of 'femmine' but few 'donne'.

Testa - head

If you’ve travelled around Italy a lot, you may have noticed that dialects in certain regions use a different word for head - ‘capo’. This comes from Latin ‘caput’, which also meant head, but in standard Italian ‘capo’ is generally used in a non-anatomical sense, for example to refer to a boss or head of department, while 'testa' refers to the body part.

The word ‘testa’ did exist in Latin, but it meant a piece of clay or pottery fragment and derived from 'texō' (to weave, to do woodwork). Over time, its meaning got extended so that it could refer to a whole pot as well as just a fragment. Then one day, someone realized that with its round shape and two side handles jutting out like ears, a Roman pot resembled a human head, so in vulgar (spoken) Latin that's what 'testa' came to mean.

Cattivo - bad

Photo: Nikki McLeod

Anyone who's tried to get to grips with Italian grammar will be well aware that ‘cattivo’ is an irregular adjective, because in adverbial form it becomes ‘male’ rather than adding the suffix ‘mente’, like most adjectives do. The origin of ‘male’ is easy to trace; it comes directly from Latin ‘malus’ (bad), so why do we now say ‘cattivo’?

In Latin, captīvus meant ‘captive’ or ‘prisoner’ (the verb ‘catturare’ (to capture) derives from the same word) but its meaning morphed over the years. ‘Cattivo’ came to mean ‘bad’ not because prisoners themselves were associated with bad behaviour, but because of the expression in Latin Christian texts 'captivus diaboli' (prisoner of the devil), referring to damned souls and sinners. You might have noticed that religion had a huge influence on the development of the Italian language, and it's no surprise since most early texts were religious and most of the earliest writers were monks.

Understanding the etymology of 'cattivo' may be helpful to foreigners trying to get their heads around where to put it in a sentence. When it follows the noun, it retains its original moral meaning ('bad' in the sense of 'evil'), so ‘un attore cattivo’ is a wicked actor, bad to their core. When 'cattivo' precedes the noun, it has a more general sense and refers directly to the noun - so ‘un cattivo attore’ might be a morally good person, but hopeless at learning their lines.

This article was originally published in 2016.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.