How the brutal murder of an anti-mafia hero altered Sicily

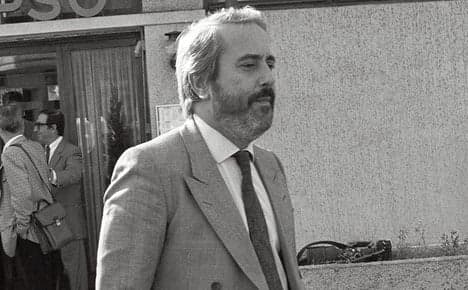

On May 23rd 1992, Sicilian judge and anti-mafia campaigner Giovanni Falcone was assassinated in broad daylight: a crime that marked a turning point on the southern island.

Falcone was killed by a bomb was placed under his car on a highway near the town of Capaci.

The bomb, placed there by a hit-man from the Sicilian mafia, also killed Falcone’s wife and three police officers.

Police officer Francesco Cerami, who was 16 years old at the time, last year spoke about his memories of the tragedy.

He remembered that an hour after the attack, Palermo’s typically bustling streets were muted with shock.

“There was almost complete silence,” Cerami said.

“The only sound was people asking, ‘Did you hear? Did you hear?’ It may have happened kilometres away, but for us it felt like the bomb exploded in the centre of the city.”

Falcone, who was 53 when he died, spent most of his life trying to fight the mafia, bringing about the so-called ‘maxi trial’ in 1986-1987, which led to the conviction of 342 mafiosi. His killing was ordered by the mafia godfather, Toto Riina.

READ ALSO: Mafia godfathers can't be church godfathers, bishop rules

Falcone's death marked a symbolic turning point in public opinion about the criminal organization, according to Carina Gunnarson, a researcher of modern mafia influence in Sicily.

“Many people refer to the assassination as something that changed their perception of the mafia,” Gunnarson said. “It revealed something about them: the attacks were just incredibly brutal, and everyone was watching the images on television.”

Addiopizzo, an anti-racketeering grassroots movement, has built on Falcone’s legacy as a campaigner for justice and reform. Since 2004, the group has developed a network of businesses which publically declare their non-payment of pizzo, or protection money, to the Sicilian mafia.

A series of events took place in Sicily on Monday to mark the anniversary of Falcone's murder. Photo: Batul Hassan

Additionally, it promotes anti-corruption education, manages a fund for the victims of mafia violence and encourages the generation of a “clean economy” for locals and tourists alike in Palermo, where Falcone, the son of a state clerk, was born.

The initiative, which was founded spontaneously and anonymously by a group of seven friends unwilling to participate in the unofficial tax system, has since inspired spin-offs in Catania, Messina, and even Germany.

Addiopizzo in Palermo operates from an apartment formerly used by the mafia as a cigarette-smuggling headquarters. It was confiscated by the government in 2007, but the non-removable double-locked, iron entrance and barred windows remain as reminders of the space’s illicit history.

The payment of pizzo is a long-standing tradition in Sicily, used by the mafia to retain control of the market and the minds of the people in specific territories. The exchange allows the mafia to keep tabs on where they have allies and influence, and may be used to force businesses to engage in practices that aren’t necessarily beneficial to them, such as employing certain people or ‘choosing’ specific providers.

Laura Nocilla, president of Addiopizzo, said one of the biggest challenges they face is changing the social norm of silence which surrounds the pizzo system.

“When we started in 2004, everyone knew about the pizzo system,” Nocilla said. “The mafia had always used this system to retain economic and social control. But nobody talked about it. So we had to strategize: how could we shift the behavior of people?”

READ ALSO: At least 5,000 restaurants across Italy thought to be mafia-run

Perhaps because of the covert nature of pizzo, Addiopizzo has found young people to be the most effective messengers of anti-corruption ideas.

Ermes Nocilla, from the movement, told the story of a child who learned about pizzo as a part of his classwork in elementary school. The child went home and asked his father, a shopkeeper in Palermo, if he payed the illicit tax. The father found himself unable to answer.

“This man came to our office the next day, in tears. He was ashamed,” Nocilla said. “For children, it’s easier to break down those barriers.”

Although accurate measurement of the pizzo is extremely difficult due to unreliable reporting in surveys, Addiopizzo’s efforts are visible in the growing prevalence of businesses declaring their non-payment.

The amount of businesses affiliated with Addiopizzo has expanded to more than 1,000. Meanwhile, shops place Addiopizzo stickers in their windows to indicate their refusal to pay, and the mafia seems to respects this signal. Addiopizzo said there have been no negative repercussions for business owners who have joined the movement.

The police have even wiretapped mafia conversations which included directions to avoid attempting to collect pizzo from businesses displaying the Addiopizzo symbol for two reasons: they know they won’t receive the money, and they run the risk of being reported.

The movement’s success is largely driven by its philosophy of collectivism: when business-owners proclaim their refusal to pay pizzo together, they exercise strength in numbers and can more effectively ensure judicial and police follow-through.

But despite these major advancements, much work remains. Gunnarson said the recent economic crisis has dulled some anti-mafia momentum in Sicily, with companies focused on their own problems instead of general wrongs in society.

She also said that accusations that several prominent government ministers and organized crime leaders collaborated during a period of intense violence in the 1990s, may be holding some Italian tongues on the matter.

“For as long as people are unsure about whether the mafia or the State will win, people will keep the ‘wait-and-see’ strategy before declaring they are on one side or the other,” Gunnarson said.

By Batul Hassan in Palermo

A version of this article was first published in May 2016.

OPINION: 'Italian judges are right to remove children from mafia families'

Photo: atlanka/Depositphotos

Comments

See Also

Falcone was killed by a bomb was placed under his car on a highway near the town of Capaci.

The bomb, placed there by a hit-man from the Sicilian mafia, also killed Falcone’s wife and three police officers.

Police officer Francesco Cerami, who was 16 years old at the time, last year spoke about his memories of the tragedy.

He remembered that an hour after the attack, Palermo’s typically bustling streets were muted with shock.

“There was almost complete silence,” Cerami said.

“The only sound was people asking, ‘Did you hear? Did you hear?’ It may have happened kilometres away, but for us it felt like the bomb exploded in the centre of the city.”

Falcone, who was 53 when he died, spent most of his life trying to fight the mafia, bringing about the so-called ‘maxi trial’ in 1986-1987, which led to the conviction of 342 mafiosi. His killing was ordered by the mafia godfather, Toto Riina.

READ ALSO: Mafia godfathers can't be church godfathers, bishop rules

Falcone's death marked a symbolic turning point in public opinion about the criminal organization, according to Carina Gunnarson, a researcher of modern mafia influence in Sicily.

“Many people refer to the assassination as something that changed their perception of the mafia,” Gunnarson said. “It revealed something about them: the attacks were just incredibly brutal, and everyone was watching the images on television.”

Addiopizzo, an anti-racketeering grassroots movement, has built on Falcone’s legacy as a campaigner for justice and reform. Since 2004, the group has developed a network of businesses which publically declare their non-payment of pizzo, or protection money, to the Sicilian mafia.

A series of events took place in Sicily on Monday to mark the anniversary of Falcone's murder. Photo: Batul Hassan

Additionally, it promotes anti-corruption education, manages a fund for the victims of mafia violence and encourages the generation of a “clean economy” for locals and tourists alike in Palermo, where Falcone, the son of a state clerk, was born.

The initiative, which was founded spontaneously and anonymously by a group of seven friends unwilling to participate in the unofficial tax system, has since inspired spin-offs in Catania, Messina, and even Germany.

Addiopizzo in Palermo operates from an apartment formerly used by the mafia as a cigarette-smuggling headquarters. It was confiscated by the government in 2007, but the non-removable double-locked, iron entrance and barred windows remain as reminders of the space’s illicit history.

The payment of pizzo is a long-standing tradition in Sicily, used by the mafia to retain control of the market and the minds of the people in specific territories. The exchange allows the mafia to keep tabs on where they have allies and influence, and may be used to force businesses to engage in practices that aren’t necessarily beneficial to them, such as employing certain people or ‘choosing’ specific providers.

Laura Nocilla, president of Addiopizzo, said one of the biggest challenges they face is changing the social norm of silence which surrounds the pizzo system.

“When we started in 2004, everyone knew about the pizzo system,” Nocilla said. “The mafia had always used this system to retain economic and social control. But nobody talked about it. So we had to strategize: how could we shift the behavior of people?”

READ ALSO: At least 5,000 restaurants across Italy thought to be mafia-run

Perhaps because of the covert nature of pizzo, Addiopizzo has found young people to be the most effective messengers of anti-corruption ideas.

Ermes Nocilla, from the movement, told the story of a child who learned about pizzo as a part of his classwork in elementary school. The child went home and asked his father, a shopkeeper in Palermo, if he payed the illicit tax. The father found himself unable to answer.

“This man came to our office the next day, in tears. He was ashamed,” Nocilla said. “For children, it’s easier to break down those barriers.”

Although accurate measurement of the pizzo is extremely difficult due to unreliable reporting in surveys, Addiopizzo’s efforts are visible in the growing prevalence of businesses declaring their non-payment.

The amount of businesses affiliated with Addiopizzo has expanded to more than 1,000. Meanwhile, shops place Addiopizzo stickers in their windows to indicate their refusal to pay, and the mafia seems to respects this signal. Addiopizzo said there have been no negative repercussions for business owners who have joined the movement.

The police have even wiretapped mafia conversations which included directions to avoid attempting to collect pizzo from businesses displaying the Addiopizzo symbol for two reasons: they know they won’t receive the money, and they run the risk of being reported.

The movement’s success is largely driven by its philosophy of collectivism: when business-owners proclaim their refusal to pay pizzo together, they exercise strength in numbers and can more effectively ensure judicial and police follow-through.

But despite these major advancements, much work remains. Gunnarson said the recent economic crisis has dulled some anti-mafia momentum in Sicily, with companies focused on their own problems instead of general wrongs in society.

She also said that accusations that several prominent government ministers and organized crime leaders collaborated during a period of intense violence in the 1990s, may be holding some Italian tongues on the matter.

“For as long as people are unsure about whether the mafia or the State will win, people will keep the ‘wait-and-see’ strategy before declaring they are on one side or the other,” Gunnarson said.

By Batul Hassan in Palermo

A version of this article was first published in May 2016.

OPINION: 'Italian judges are right to remove children from mafia families'

Photo: atlanka/Depositphotos

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.